Hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) refrigerants are the current choice for most of the U.S. air conditioning industry and for a good reason. Many of the HFC refrigerants used today are non-ozone depleting, non-flammable, recyclable and energy-efficient. While HFCs have good environmental properties and promote energy efficiency, many are now also considered to be global warming gases due to their relatively high Global Warming Potential (GWP).

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) began regulating HFC refrigerants in 2015 with the introduction of the Significant New Alternatives Policy (SNAP). Since then, the industry has made significant progress in identifying the next generation of low-GWP refrigerants. However, the events of the past two years leave the timing of the transition uncertain.

U.S. Court Vacates SNAP Rule 20

In August 2017, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit ruled to vacate EPA SNAP Rule 20. Responding to a challenge submitted by two refrigerant manufacturers, the court ruled that the EPA had exceeded its authority to require the replacement of HFCs under Section 612 of the Clean Air Act.

The decision was based on the reasoning that Section 612 was created to curb substances containing higher ozone depletion potential, not to address the matter of greenhouse gases and their associated GWPs. The decision was appealed to the Supreme Court, who declined to consider the case.

In response to SNAP Rule 20 being vacated, the EPA has stated that it will no longer enforce refrigerant delisting and will roll back other HFC-related regulations. In particular, the EPA will exclude HFCs from the leak repair and maintenance requirements for stationary refrigeration equipment, otherwise known as Section 608 of the CAA .

The updated rule, which had been in effect since 2016, lowered the leak rate threshold in supermarket refrigeration systems from 35 percent to 20 percent and set forth specific requirements pertaining to HFC management. With the rescinding of this rule, refrigeration equipment with 50 pounds or more of HFC refrigerant would no longer be subject to these requirements.

Even if the leak repair and maintenance requirements of Section 608 is no longer enforced for HFC systems, an effective leak repair and maintenance program is still generally recognized as an industry best practice. Other beneficial provisions of Section 608 — including the certified technician program and the refrigerant recovery and reclamation rules — are still in effect.

There is currently no mechanism in place for the EPA to regulate refrigerants based upon GWP. The U.S. has not yet ratified the 2016 Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol, a global treaty created to phase out harmful greenhouse gases and ozone-depleting substances, thus leaving us with no federal solution. One option is to pass federal legislation giving the EPA the authority to regulate HFCs. A federal bill has now been proposed.

The American Innovation and Manufacturing Act of 2019

The AIM Act of 2019 (S. 2754) was introduced in the Senate by Senators John Kennedy and Tom Carper in October 2019. As of January 1, 2020 there were 32 co-sponsors, divided equally Republican and Democrat. If passed, this bill would authorize the EPA to regulate HFCs and specify production and consumption limits over 15 years. This bill is not tied to the Clean Air Act and would not preempt states from implementing their own phase down schedule. Multiple HVACR industry associations have signed a letter in support of the AIM Act recognizing the potential economic and consumer benefits. A similar bill has now been introduced in the House.

California Air Resources Board (CARB) HFC phase down

With federal efforts to regulate HFCs stalled in 2017, the California Senate directed the California Air Resources Board (CARB) to preserve the original framework outlined in EPA Rules 20 and 21. CARBs proposal also calls for more aggressive phase-down measures in line with the EU’s fluorinated greenhouse gases (F-gases) efforts.

The first CARB proposal preserved the federal framework in new retail food refrigeration, food dispensing equipment, refrigerated vending machines, chillers, and foams.

The second proposal calls for future rules on refrigerant use according to their GWP and refrigerant charge in specific applications. Under these guidelines:

- Refrigerants with a GWP of 750 or more would be prohibited in chillers beginning in 2024.

- Refrigerants with a GWP of 750 or more would be prohibited in new stationary air-conditioning systems beginning in 2023.

Approved by the board, CARBs Rulemaking 1 proposals to adopt SNAP Rules 20/21 entered effect in 2019. Draft regulation regarding CARB’s Rulemaking 2 proposals was released in January 2020. If the second rulemaking enters effect, California will be the first state to require the transition to a low GWP refrigerant.

Other States Follow Suit in Adopting SNAP Rules 20 and 21

In response to the U.S. government’s decision to withdraw from the Paris Agreement several governors joined together to form the United States Climate Alliance. The group now consists of 25 members committing to contribute to the global effort to address climate change, specifically upholding the goals of the Paris Agreement and reducing greenhouse gas emissions by at least 26 percent by 2025.

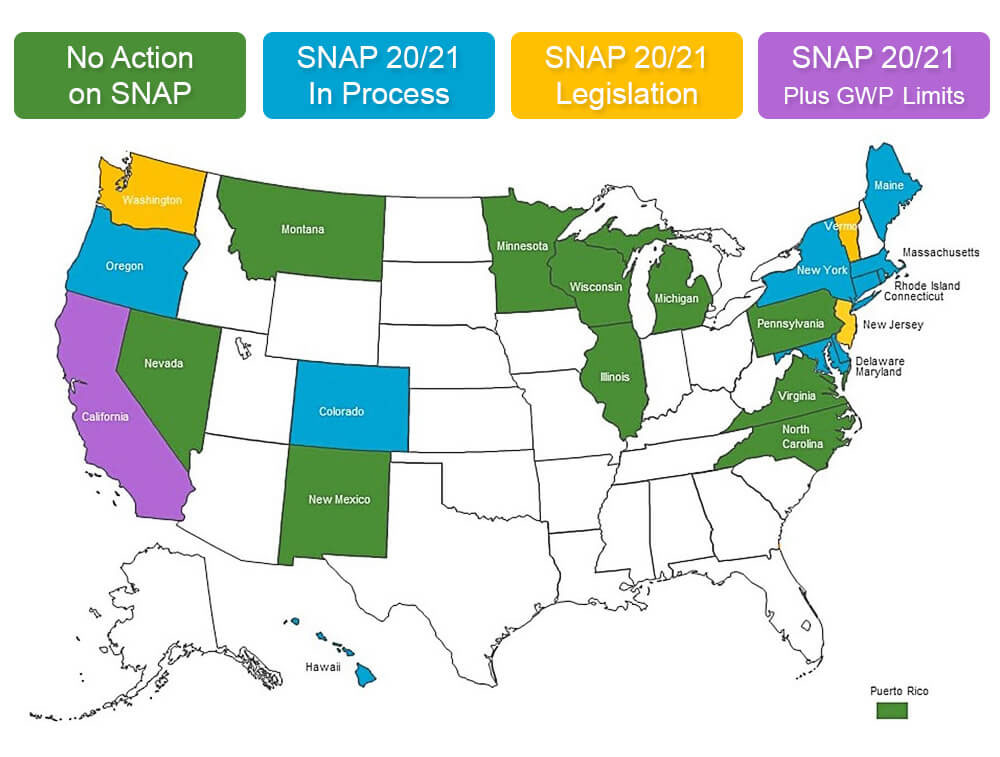

Adopting SNAP Rules 20 and 21 at the state level is one mechanism to achieve that goal. Thus, Washington, Vermont, and New Jersey have also adopted SNAP 20/21 through legislation, with several other states announcing they too would begin to phase out HFCs.

Standards and Codes

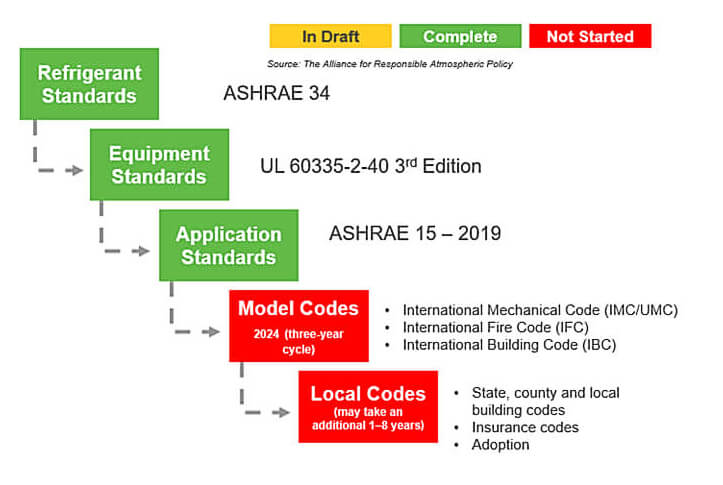

Many of the new low-GWP refrigerants are classified as A2L, or mildly flammable by ASHRAE standard 34. The most recent editions of ASHRAE standard 15 and UL standard 60335-2-40 have been modified to allow the use of A2Ls in residential and commercial HVAC applications. However, model codes have yet to adopt these changes, and the next code cycle is not until 2024.

Building codes vary from state to state and in some cases town to town, and local code adoption to allow the use of flammable refrigerants in comfort cooling may take years to accomplish. However, states wanting to enable the use of lower GWP refrigerants sooner could choose to adopt parts of ASHRAE 15-2019 directly into state building codes and recognize UL 60335-2-40 3rd edition as Washington State has done. Added to the patchwork of regulation above, it is foreseeable that it may be mandatory to use a low-GWP refrigerant in one state but illegal due to building codes in another neighboring state. Contractors will be left to educate the homeowner on the requirements and potential cost implications.

Factoring Energy into the Regulatory Equation

HFC Refrigerants are only one factor in the regulatory equation. The HVACR industry is also dealing with energy mandates from the Department of Energy (DOE). Both residential and commercial air conditioning and heat pump sectors will see new energy efficiency regulations effective January 1, 2023. These efficiency increases will need to be met with both the existing refrigerant and the new low GWP refrigerant, leading to a larger testing burden than is typically experienced during a refrigerant or efficiency transition.

As a Contractor, What Does This Mean to Me?

Refrigerant regulations are coming – the question is when and how, and that depends on the state(s) in which you do business. The combination of state by state HFC regulation and building code adoption could lead to a proliferation of refrigerants as some states begin restricting HFC refrigerants, while neighboring states/localities remain status quo. It will be important to stay up to date with your state and local building codes and HFC regulations to ensure you are compliant.

The contents of this article are presented for informational purposes only, and the contents are not intended to be a substitute for legal advice. Emerson Climate Technologies, Inc. or its affiliates (collectively “Emerson”) has made every attempt to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information provided in this article. However, the information in the article is provided “as is” without warranty of any kind. Emerson does not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article.

Read Next: Back to School: The Contractor’s Guide to Continuing HVAC Education